Antico: The Golden Age of Renaissance Bronzes

May 1, 2012, through July 29, 2012

|

|

Hercules

Model created by 1496,

cast possibly by 1496

Bronze with fire gilding and silvered eyes

Original bronze base

The Frick Collection, New York,

Gift of Miss Helen Clay Frick

|

Hercules is depicted as an aged demigod, crowned

and bearing the symbols of his labors. He rested his

right hand on a club (lost) and held the apples of the

Hesperides in his left (lost). The lion skin, which is

slung around his arm and hips, recalls the drapery

worn by Jupiter, his divine father. The lion's mask

creates a snarling counterpoint to the hero's calm.

Hercules' abundant locks and beard are sharply

tooled, and each hair on the beast's pelt is incised

into the metal. This splendid statuette still retains

much of its black patina, brilliant gilding, and

silvering. Probably created for Ludovico Gonzaga,

it is the earliest and finest surviving version.

|

|

Hercules

Model created by 1496,

cast probably after 1519

Bronze with silvered eyes

Original bronze base

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna,

Kunstkammer

|

Hercules was among Antico's most popular

statuettes. Two of the four surviving versions are

exhibited here. This figure retains the club missing

from the nearby Frick example. The hard, blocky

rendering of the musculature, face, and hair and

the absence of detail on the lion's pelt suggest that

it is a late cast probably executed by a master

other than Antico. Late statuettes often lacked

gilding, and had simpler surfaces and silver eyes

that are characteristic of ancient small bronzes.

The demigod Hercules symbolized princely virtue.

Probably all of Antico's Gonzaga patrons owned

an example of this work.

|

|

Probably Roman

Hercules

2nd–3rd century ad, probably restored in the 15th century

Bronze with copper inlay and traces of gilding

Modern flat bronze base

Musée du Louvre, Paris, Département des

Objets d'art, Legs Gatteaux

|

Although Antico restored classical marble statues and

busts that often served as models for his sculptures,

no large-scale antique prototype for Antico's Hercules is known. Recent technical analysis suggests that this

statuette, long thought to be sixteenth century, might

be a classical fragmentary bronze to which missing

parts were added. The head and torso are one piece.

The inlayed silver eyes and copper nipples are typical

of ancient sculptures. Did Antico, who was a master

of the classical indirect casting method, restore

this bronze and use it as a model for his Hercules

statuette? It is exhibited with Antico's works for the

first time for comparison and study.

|

|

Cupid

Probably by 1496

Bronze with fire gilding and silvered eyes

Modern stone base and golden

hemispherical support

Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence,

Carrand Collection

|

Antico depicts the god of sensual love about to

launch an arrow at a hapless victim. The missing bow

and arrow are almost unnecessary. Beauty is Cupid's

weapon. The god floats on one foot, his plump body

impossibly lifted by tiny wings that catch the air.

Antico has indulged his wit in an early statuette

that is not an antique reconstruction. He proclaims

his prowess in bronze by balancing the figure on a

single point. He lavishes his goldsmith's skills on the

superbly tooled and burnished hair, feathered wings,

and quiver. Everything about this delightful figure

entices the viewer to approach, coming close enough

for love's dart to strike.

|

|

Apollo Belvedere

Model created and cast c. 1490

Bronze with fire gilding and silvered eyes

Original bronze base;  (Antico)

inscribed on quiver strap

Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung,

Frankfurt am Main

|

Apollo steps forward, sighting down an arrow

released from his bow (lost). The unearthing near

Rome of the marble Apollo Belvedere in 1489

was the find of the century. Antico was the first

artist to interpret the monumental ancient statue

in this, one of his earliest statuettes and the only

signed one. He captures the likeness of the marble

god with archeological precision and restores the

missing right forearm and hands to complete the

work. Antico eliminated the marble statue's treetrunk

support, animating Apollo's stride. The

combination of a black patina, partial gilding,

and silvered eyes is Antico's signature invention.

Although without direct antique precedent, the

opulent surfaces of his bronzes revive the splendor

of classical art.

|

|

Apollo Belvedere

Cast c. 1502

Bronze with fire gilding and silvered eyes

Original bronze base; bow later addition

Galleria Giorgio Franchetti alla Ca' d'Oro,

Venice

|

At least ten years separate the making of these two

masterpieces. Their differences reveal the evolving

Renaissance concept of classical male beauty. In 1498

the molds Antico used to cast the first Apollo were

stolen; this later version is a complete rethinking of

the earlier work and was probably modeled afresh

in the sixteenth century. This Apollo is broader

in proportion and more muscular than the first.

His amplitude contrasts with the earlier figure's

compactness. His features are sensual, the other's

are classically refined. His loose curls and drapery

respond to his movement. He seems to stride,

whereas the earlier Apollo steps forward.

|

|

Venus Felix

Model probably created by 1496, cast c. 1510

Bronze with fire gilding and silvered eyes

Ebony base inset with ancient coins, late 16th–17th century

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Kunstkammer

|

In this masterpiece Antico interprets the famed Venus Felix, an ancient marble statue of the founding goddess of imperial Rome. Unlike the sedately posed classical figure, Antico depicts Venus gathering her drapery to walk forward. The loosened cloth flutters along her leg and feet and falls beneath her hips to reveal her torso and buttocks. The exceptionally preserved black patina emphasizes the suppleness of Venus's flesh. Flawless, burnished gilding highlights the drapery's motion. Antico was the first Renaissance sculptor to explore the subject of the idealized female nude. Six of his seven greatest works in this genre are in the exhibition.

|

|

Emperor Marcus Aurelius on Horseback

Model created by 1496, cast c. 1519–28

Bronze with oil gilding and silvered eyes

Sammlungen des Fürsten von und zu

Liechtenstein, Vaduz-Vienna

|

Impassive, erect, and unmoving, the emperor

controls his fiery pacing steed with absolute

command. Antico's statuette is the most accurate

Renaissance reproduction of a famous equestrian

monument that was the only ancient bronze to

have been on view in Rome since the age of the

Caesars. His Gonzaga patrons probably each

owned a version of this "marvel of Rome" that

associated their rule with a magnificent imperial

heritage. Antico inventively revives the classical

monument's splendor by imagining how the ancient

metal's corroded green surface would have looked

embellished with black, gold, and silver. This cast is

the sole surviving example.

|

|

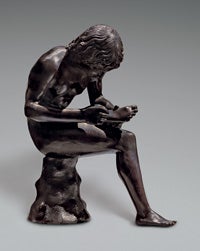

Spinario

Model created by 1496, cast possibly 1499

Bronze with silvered eyes

Private collection

|

The Spinario (thorn puller) was an esteemed ancient Roman bronze. In Antico's day the life-size statue was displayed on a column on the Capitoline Hill as a monument to Rome's enduring legacy. In 1501 Isabella d'Este placed a version of this statuette high on the cornice of a doorway within the room containing her collection of ancient and modern works. Absorbed by his task, the youth unselfconsciously presents his face and body for the viewer's delectation from below. Antico was the earliest artist to capture the grace of this figure in an independent bronze. Isabella probably later commissioned the Seated Nymph (displayed nearby) to be the Spinario's companion over the opposite doorway.

|

|

Meleager

Model and cast probably by 1496

Bronze with fire gilding and silvered eyes

Original bronze base

Victoria and Albert Museum, London,

Purchased from the Horn and Buyan Bequests

with the assistance of a contribution from

The Art Fund

|

This masterpiece derives from a battered Roman marble that, by Antico's day, was headless, limbless, and eroded by the effects of time. From the fragment Antico invented a complete figure and revived the mythical drama of Meleager killing the Calydonian boar. With gold tunic fluttering, teeth bared, and silver eyes widened in attack, the hero delivers the death thrust with his spear (lost) in a graceful movement that is as exquisite as the statuette's precisely finished details. The well-preserved black patina provides a smooth, dark counterpoint to the tooled and burnished golden drapery and tousled hair. The swirling cascades of Meleager's cloak are a

tour-de-force of contrapuntal rhythms.

|

|

Pan

Model created probably by 1499, cast probably after 1519

Bronze Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Kunstkammer

|

Pan, a rustic satyr deity, ruled the material world and personified man's deepest passions. Antico closely based his figure on an ancient Roman marble group of Pan and the shepherd Daphnis. The missing recipient of the satyr's lustful attentions was probably a version of this youth. The glacial hardness of Pan's muscles, the exaggerated modeling of the face, hair, and fur—as well as the lack of gilding—suggest that this is a late cast. In the Gonzaga collections Pan and his lost companion probably sat on a shelf, leaning forward with legs out-thrust. Thus seated they introduced Nature's irrepressible sensuality into rooms dedicated to the life of the mind.

|

|

Seated Nymph

Model probably created and cast 1503

Bronze with fire gilding and silvered eyes Original bronze base

Robert H. and Clarice Smith

|

The Nymph sits relaxed yet attentive, leaning forward over angled limbs, rounding her back in a sinuous curve. Antico plays the dark simplicity of the nude figure against the golden complexities of drapery and intricately coiffed hair. Conceived to be beautiful from every point of view, the Nymph is one of Antico's most ambitious statuettes. It is also his smallest. The jewel-like precision of detail reveals his goldsmith's training transferred to the bronze medium. Gazing outward with lips parted, the figure expresses poetic longing with remarkable intensity for a work so small. Isabella d' Este probably received this exquisite Nymph as companion to her Spinario.

|

|

Seated Nymph

c. 1503–11

Bronze with fire gilding and silvered eyes Original bronze base

Private collection

|

Antico pioneered indirect casting, a technique

that allowed him to reproduce his sculptures. The Seated Nymph was extremely popular. Of the many

surviving variants, only the adjacent Nymph and

this recently discovered example were cast during

his lifetime. Their unprecedented comparison

reveals the small, significant differences that can

exist between bronzes deriving from wax models

made from the same molds. This Nymph's drapery

and hairstyle are simpler than the other's. She

wears a plain diadem; the other's hair is pulled in

an elaborate knot over her brow. Antico's bronzes

were often produced by trusted masters who

modeled details in the wax before casting. All such

finished statuettes were considered to be Antico's,

challenging our modern concept of authorship.

|

|

Atropos

Model created c. 1500,

cast c. 1500–1511

Bronze

Modern base

Victoria and Albert Museum, London,

Bequeathed by Sir Otto Beit

|

Atropos, one of the three Greek Fates, cuts the thread

of life. In her raised hand she grasps a "bozzolo" (silk

cocoon) that may be a pun associating this work with

Antico's Gonzaga patrons who held court at Bozzolo

castle. From the cocoon a wire thread presumably

fell straight to her lowered hand, which holds the

remains of scissors. Antico probably based this

figure on an ancient small-scale sculpture of Venus

the Sandalbinder. The bronze surface is exquisitely

worked, and tiny details like the ringlets and pearl

headdress encourage a close viewing. Atropos's turning pose reveals her beauty — fragile as the living

thread she severs — from every point of view.

|

|

Atropos

Model created c. 1500–1511, cast probably after 1519

Bronze with silvered eyes

Original bronze base

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Kunstkammer

|

Antico's command of the indirect casting method allowed him and trusted colleagues to reproduce versions of his statuettes. This nude has the sharply realized forms typical of late bronzes nearby. She lacks her earlier counterpart's pearl headdress and attributes. Her nobly detached expression is different from the other's delicate pathos. Never intended to be seen together, these statuettes' unprecedented juxtaposition emphasizes each figure's individuality and mood. Under the master's guidance, reproduction brilliantly surpassed mere copying.

|

|

Mercury

Model created and cast c. 1500–1511

Bronze with fire gilding and silvered eyes

Original bronze base

Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence

|

Mercury, lost in thought, languidly rests his arm on a rustic golden staff. Heroically muscular, yet utterly relaxed, the youthful god is exquisitely balanced in a hip-shot pose that denies the potential for swift movement. Antico does not depict the flying, wing-footed messenger of classical myth. This is astrological Mercury, who ruled over scholarly and artistic pursuits. Antico's planetary deity is crowned with wings on his brow — the source of the mind's activity. In the Gonzaga collections statuettes were often placed on shelves and cornices above eye level. Mercury points his finger and directs his gaze downward, prompting the viewer's intellectual journey.

| |

Hercules and Antaeus

Model created by 1511, cast 1519

Bronze

Original bronze base, inscribed on the

underside: D/ISABEL/LA/ME/MAR (Divine Isabella

Marchesa of Mantua)

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna,

Kunstkammer

|

Hercules heaves Antaeus off the ground, breaking

his back against his shoulder. Antico reconstructs

a Roman marble fragment as a freestanding group

that is dynamic from every viewpoint. In 1519,

when Isabella d'Este requested versions of statuettes

that Antico had made long ago, he proudly noted

that the "Hercules killing Antaeus" was the "most

beautiful." Securely dated and documented by

inscription to Isabella's collection, this statuette

provides the stylistic reference point for late casts

that were made from Antico's earlier models. Its

slick surfaces, robust modeling, and lack of gilding

are typical late characteristics. Antaeus's hairstyle

and anguished features are Antico's inventions; the

head is similar to the earlier Meleager's nearby.

|

|

Paris

Probably after 1511

Bronze with fire gilding and silvered eyes The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Edith Perry Chapman Fund, 1955

|

In a contest of beauty the Trojan prince Paris awarded Venus the golden prize. His choice led to the fall of Troy and the founding of Rome. His abstract nudity, golden halo of curls, and distant gaze endow him with a numinous aura. Antico satisfied his Gonzaga patrons' claims to Rome's ancient heritage by depicting Paris in the guise of a classical god. Late in his career Antico rethought his approach to statuettes, inventing grandly scaled figures that were without direct ancient prototypes. The only surviving two, displayed here, are most closely related in style to late busts, like Bacchus nearby.

|

|

Venus

Possibly c. 1520–28

Bronze with fire gilding and silvered eyes

Oil lamp and brown lacquer patina later additions

The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

|

The goddess of love is posed in classical contrapposto, resting her weight on one foot with her hips and shoulders rising and falling in counterpoint. Her large silver eyes stare from beneath regally crowned golden tresses. Antico depicts Venus in her role as divine mother of ancient Rome in a late statuette that is his own invention. Sensuously present yet ideally remote, his majestic portrayal of the founding goddess is as close as he would ever come to creating an ancient idol. It has been suggested that Antico made Venus and the adjacent Paris as a narrative pair. |