Cimabue and Early Italian Devotional Painting

October 3 through December 31, 2006

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Cenni di Pepo (c. 1240–c. 1302), known as Cimabue, The Virgin and Child Enthroned with Two Angels, c. 1280, tempera on poplar panel, National Gallery, London |

|

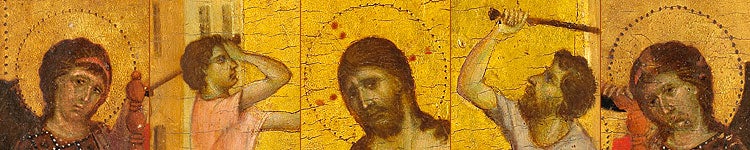

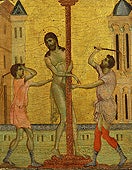

Cimabue, The Flagellation of Christ, c. 1280, tempera on poplar panel, The Frick Collection,

Photo credit: Michael Bodycomb

|

|

|

|

|

The artist Cenni di Pepo (c. 1240 – c. 1302), known as Cimabue, has long been considered one of the founders of Italian Renaissance painting. He and his contemporaries endowed their works with greater emotional expression and a more naturalistic approach than previous generations, revolutionizing Italian art during the late thirteenth and the first half of the fourteenth century. The Frick Collection is fortunate to possess a painting by Cimabue, The Flagellation of Christ, purchased by the trustees in 1950. Although the panel was acquired as a work by Cimabue, over the next half century scholars debated whether it was painted by him or the Sienese master Duccio di Buoninsegna (c. 1255 – 1319). Six years ago, the original attribution of The Flagellation of Christ was confirmed by an extraordinary discovery. A panel known to be by Cimabue emerged on the art market in Britain, and technical studies revealed that it once had formed part of the same larger painted ensemble as the Frick panel.

Now part of the collection of the National Gallery in London, this painting, The Virgin and Child Enthroned with Two Angels, will be reunited with the Frick’s Flagellation for the first time in America in this Cabinet installation. Visitors to the Frick will have the rare opportunity to see these two jewel-like panels together, and to appreciate Cimabue’s delicate miniaturist technique in these works, which are his only known small-scale paintings. A selection of panels, manuscripts, and verre églomisé (painted and gilded glass) on loan from New York collections also will be on view, illustrating the various forms of small-scale devotional art with which Cimabue and his contemporaries experimented.

At first glance, the two Cimabue panels appear different, owing to the presence of a modern-day varnish on the National Gallery panel. Their carpentry, condition, style, and technique, however, attest to their origins as part of the same work, either a small altarpiece, diptych, or triptych. The grain of the wood, the thickness of the panels (both of which have been thinned down since they were first painted), the pattern of craquelure in the paint, and even the worm holes in the wood are comparable. Both feature a similar border in the gold ground, consisting of two rows of pinprick-like punches surrounding a delicate scroll pattern formed by tiny punch marks.

|

|

| Detail of craquelure (National Gallery painting) |

Detail of craquelure (The Frick Collection painting) |

Such parallels between the Virgin and Child and the Flagellation confirm that both were once part of the same work. At an unknown date, the larger ensemble was cut apart, probably so that smaller pieces of it could be sold as individual works, a fate that befell many early Italian pictures during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. On the Flagellation, the painted surface stops short of the edge of the panel and curls upward with raised edges (barbes) at the bottom and right sides, indicating that it once was framed on those two sides and therefore must have been positioned at the lower-right corner of a larger painted panel. Similarly, the left side and top of the Virgin and Child is barbed, indicating that it formed the upper-left corner of the same work.

But what was in between? Were the National Gallery and Frick panels originally at the upper-left and bottom-right corners of a single panel, or were they portions of different panels that were part of the same multi-panel ensemble? How large was the original work, and how many scenes did it contain? These questions remain unanswered, as the two panels do not constitute enough pieces of the puzzle to allow for its definitive solution.

The painted ensemble that once included the two Cimabue panels was designed to be used as a visual aid during individual or small-group prayers and/or religious celebrations. The two panels seem to be telling opposing stories: one of glory and beauty, the other of vulnerability and violence. The central figure on the National Gallery panel is Mary, regally cloaked in a lapis blue robe. She sits on an intricately carved throne, attended by angels dressed in tunics trimmed in rich embroidery and delicate pearls. On her lap, she holds the curly-headed Christ Child, whose soft-fleshed arms reach toward her outstretched hand. By contrast, the focus of attention on the Frick panel is a thin, nearly naked Christ tied to a marble column. Instead of angels waiting on him, two standing figures in profile beat him with whips as he gazes out toward the viewer with an expression of quiet anguish. Together, the paintings contrast Christ’s heavenly origins with his earthly suffering.

Although vastly different in emotional tenor, both panels emphasize Christ’s humanity, a theme particularly important to members of the Franciscan Order, the most powerful religious group in Italy during the thirteenth century. In literature and art, the Franciscans emphasized the stories of Christ’s Infancy and his Passion. The fact that the lost Cimabue work contained at least one scene each from Christ’s Infancy and Passion points toward the patronage of the Franciscans, who commissioned Cimabue several times throughout his career to execute monumental panels and frescoes in Pisa, Florence, and Assisi.

In Cimabue’s day, the Franciscans and other religious groups encouraged pious people to imagine themselves interacting with Christ and participating in the events of his life, events to be relived daily in the imagination during meditation. Painted panels and other images heightened this sense of participatory devotion, and the convincing naturalistic representation Cimabue achieved in the Frick and National Gallery panels would have reinforced the impact and immediacy of the religious narratives.

The fact that The Frick Collection owns the Flagellation — the only painting by Cimabue in the United States— may seem surprising since Henry Clay Frick did not collect Italian gold-ground paintings and, in general, eschewed religious works in favor of portraits and landscapes. His daughter, Helen Clay Frick, however, had a particular interest in early Italian pictures. Her love for Italian art had been nurtured by a visit to Italy during the winter of 1923/24 and again in the summer of 1925. Miss Frick chronicled her travels in scrapbooks in which she pasted carefully labeled photographs and postcards, annotated with commentaries on the works of art she had seen. A postcard of Cimabue’s Santa Trinita Madonna (Uffizi Gallery, Florence) is among the images collected from her Florentine sojourn.

|

| Scrapbook assembled by Helen Clay Frick (1888–1984) following her 1923/24 trip to Italy. The center image shows Cimabue’s Santa Trinita Madonna (Uffizi Gallery, Florence). The Frick Collection / Frick Art Reference Archives |

A few months after Miss Frick returned from Italy in early 1924, the Board of Trustees authorized her to purchase The Frick Collection’s first early Italian Renaissance painting, The Annunciation by Fra Filippo Lippi. Over the next three decades, Miss Frick served as chair of the acquisitions committee, and under her leadership the Frick gradually assembled a small but extremely important group of Italian primitives, including the Cimabue Flagellation. When the painting was offered to the Frick for sale in 1950 by the dealer Knoedler & Company, Miss Frick and the other members of the acquisitions committee unanimously agreed on the panel’s rarity, quality, and beauty and immediately sought to acquire it. By February 1, 1951, the Flagellation was on view at the Frick, and that morning the New York Times heralded it as “the best of the rare thirteenth-century Italian paintings in America.”

Without question, the Frick and National Gallery panels rank among the finest known works of thirteenth-century painting. The engaging expressions of Christ, the Virgin, and the angels combined with the delicacy of their execution attest to Cimabue’s ability to create powerful, timeless images truly revolutionary for their day. The panels are emblematic examples of Cimabue’s genius and, after seven centuries, still have the power to connect celestial glory to earthly experience. — Holly Flora, Curator, Museum of Biblical Art, New York

Cimabue and Early Italian Devotional Painting was coordinated for The Frick Collection by Holly Flora, Curator, Museum of Biblical Art, in conjunction with the Frick’s Associate Curator Denise Allen. The exhibition has been generously underwritten by Jon and Barbara Landau. Additional support has been provided by The Council of The Frick Collection and The Helen Clay Frick Foundation. The accompanying publication is made possible, in part, by Lawrence and Julie Salander.

|