Renoir, Impressionism, and Full-Length Painting

February 7 through May 13, 2012

| |

|

|

|

| |

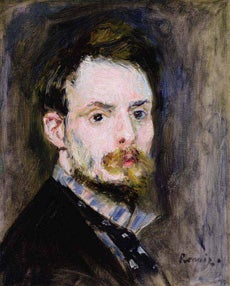

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1875 |

|

|

The Impressionists

When we think of the Impressionists,

who turned their backs on the official

Salon in the 1870s and 1880s and

showed their work in dealers' galleries,

we conjure up light-filled, freely painted

landscapes and scenes of modern life.

Impressionist paintings also tend to be

relatively modest in scale, spontaneous

in compositional structure, and of a

brightness and tonality which, while

admired today, caused distress and incomprehension among

many critics and collectors at the time. The young painters

who joined forces in the spring of 1874 to mount the First

Impressionist Exhibition — chief among whom were Claude

Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro,

and Paul Cézanne — had been encouraged in the 1860s by

Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet to present their work in

the official arena. In the last decade of the Second Empire, these

Young Turks had even enjoyed a certain notoriety at the Salon,

garnering attention in the press, interest from dealers, as well

as the occasional sale. To make an impact in the official Salon,

held every year in the crowded rooms of the Palais de l'Industrie

on the Champs-Élysées — replaced in 1900 by the Grand Palais — these artists were encouraged to paint works that today might

be described as having "wall power."

| |

|

|

|

| |

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Self-Portrait, The Sterling and Francine Clark Art

Institute, Williamstown c. 1875 |

|

|

The large-scale format was especially congenial to Renoir, who

as an eighteen-year-old had apprenticed with a manufacturer of

blinds for export to missionary churches and had painted full-length

images of the Virgin and Child in imitation of stained glass

windows. Renoir had also painted mural decorations in cafés

in his youth, working directly on the walls. "You have no idea

how intoxicating it is to cover large surfaces," he later confided

to his son, the filmmaker Jean Renoir. Between the mid-1860s

and the mid-1880s, when Renoir and the artists who came to

be known as the Impressionists were constructing a new

pictorial language, he was constantly engaged in painting, or

thinking about painting, large, figurative compositions in the

time-honored tradition of the masterpiece. For much of this

time, Renoir was preoccupied with showing his work in the

official Salon, to which — between 1863 and 1883 — he submitted

every year but three. Only in 1874, 1876, and 1877 did Renoir

show his paintings in the Impressionist group exhibitions; in

1882, much to his distress, his dealer Paul Durand-Ruel sent

twenty-five of his works to the Seventh Impressionist Exhibition

without his authorization.

The nine works, dating from 1874 to 1885,

demonstrate the importance of large-scale

figure painting in Renoir's

oeuvre, above all in the experimental

decade of Impressionism when such

formats and fashionable subjects were

also the stock-in-trade of successful

genre painters working in more

conventional and conservative styles.

The exhibition was inspired by La

Promenade of 1875–76, exhibited in the Second Impressionist

Exhibition of April 1876 and acquired by Henry Clay Frick in

1914. Hanging in a collection that boasts splendid

full-length paintings by Veronese, Van Dyck, Gainsborough,

and Whistler, Renoir's Promenade appears as the most modern

example of a well-established tradition in portraiture and history

painting. As this group of nine full-length figure paintings shows,

Renoir — a committed Impressionist — returned to this "public"

format again and again for his most ambitious paintings of

modern life. Few of these works, now considered among the icons

of Impressionism, sold for large sums at the time; some remained

unsold for decades. Nor were any of the paintings in the exhibition

commissioned by patrons or dealers. Only in the 1890s, when the

Impressionists had long since disbanded, did collectors of modern

art begin to acquire these earlier works for respectable amounts.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, American collectors

such as Frick, Joseph Early Widener, and Stephen C. Clark

purchased outstanding examples of Renoir's full-length figure

paintings for record prices, prices that nevertheless remained well

below those fetched by the work of the established Old Masters.

Principal funding for the exhibition is provided by The Florence Gould Foundation and Michel David-Weill.

Additional support is generously provided by The Philip and Janice Levin Foundation, The Grand Marnier Foundation, and the Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation.

Corporate support is provided by Fiduciary Trust Company International.

The exhibition is also supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. |