Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (1724–1780)

October 30, 2007, through January 27, 2008

Selected Images from the Exhibition

|

|

Germain-Augustin and Rose de Saint-Aubin,

Drawn by Their Uncle,

1766

Brush and gray wash, over black chalk and graphite

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

|

Saint-Aubin seems to have found some measure of ordinary family life in the home of his widowed older brother, Charles-Germain, father of the two children portrayed here. Rose (1755–1813), as the girl was nicknamed, holds a hurdy-gurdy in her lap, as though she were just preparing to play. Her brother Germain Augustin (1758–1825), sporting a stylish cap, possesses an aura of quiet self-confidence belying his eight years.

|

|

The Triumph of Pompey (61 BC),

1765

Watercolor and gouache, pen and black and brown inks, black chalk, and graphite

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

|

In his representation of the Roman general Pompey’s third and final triumphal entry into Rome amid a seemingly endless procession of troops, trophies, revelers, and conquered enemies, Saint-Aubin incorporates an anecdote described by Plutarch with reference to Pompey’s initial triumph in 79 b.c. Riding grandiosely on four elephants, he was unable to pass through the city gates and had to switch to a horse. In Saint-Aubin’s careful delineation of eight tusks and four trunks, his sense of humor prevailed over his scruples as an historian.

|

|

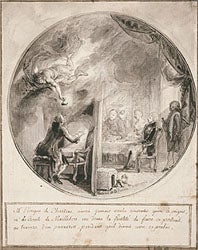

Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, Concealed

Behind a Screen, Making a Portrait of the

Bishop of Chartres,

1768

Pen and black ink, brush and gray wash over graphite

The Art Institute of Chicago

|

Saint-Aubin here records an unusual commission he received from the comte de Maillebois. As described in the inscription, the artist was engaged to hide behind a screen at a dinner party and secretly prepare a portrait of the Bishop of Chartres. We see Saint-Aubin and his inspiring genius on one side of the screen opposite the co-conspirators seated at dinner with the unsuspecting bishop. A yapping dog warns of the artist’s presence, directly above the signature of his name.

|

|

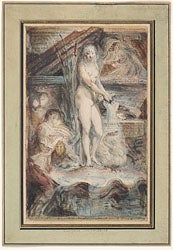

Allegory in Honor of the Death of Voltaire,

c. 1779

Black chalk, brown ink, and watercolor

Rijksmuseum, Rijksprentenkabinet, Amsterdam

|

This funerary allegory commemorates the death of Voltaire on May 30, 1778, three months after his return to Paris following an absence of twenty years. A nymph pours water into a large conch, indicating the overturned hourglass with her left hand. Still writing, Voltaire appears behind the rim of the sarcophagus, finally silenced by the figure of Death. The muse in the left foreground is shown writing the maxim that was inscribed on Voltaire’s mausoleum at Ferney: HIS SPIRIT IS EVERYWHERE, BUT HIS HEART IS ONLY HERE.

|

|

The Flirtatious Conversation,

1760

Watercolor and gouache

Museum of Fine Arts, Forsyth Wickes Collection, Boston

|

In this “painted drawing” intricately layered with watercolor and gouache, Saint-Aubin tells a little story explained in verses of his own composition: “Old, unreformed debauchee / You think you are seducing this beautiful creature / But long ago the damsel/Made up her mind to be honorable.” The open jewelry case on the mantel suggests her motive for feigning availability.

|

|

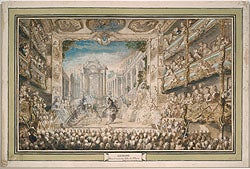

Quinault and Lully’s Opera “Armide” Performed at the Palais Royal Opera House, 1761

Pen, watercolor, and gouache over graphite

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

|

Saint-Aubin commemorates the love duet in Act V, Scene 1 of the opera Armide. Despite the date given on the mount, this is the production of 1761, with sets designed by François Boucher and his son. He also gives a view of the Palais-Royal opera house, soon to be destroyed by fire in 1763, and a witty analysis of audience behavior.

|

|

A Street Show in Paris,

1760

Oil on canvas

National Gallery, London

|

Saint-Aubin’s most celebrated painting shows an assortment of strollers and passersby who stop to watch Harlequin and Crispin, characters from the commedia dell’arte, dueling on the raised wooden platform. The audience is witnessing a parade, an open-air entertainment staged outside the entrance of a theater to entice the public inside. Saint-Aubin’s portrayal of this boisterous performance is surprisingly lyrical, and his rear-view silhouettes of elegantly clad women call to mind the aristocratic protagonists of Watteau’s fêtes galantes.

|

|

Momus

1752

Red, black, and white chalk

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

|

This large figure drawing in trois crayons shows a muscular ballet dancer in the role of Momus — the offspring of Night and Sleep, whom Jupiter had expelled from Olympus for his relentless mockery and derision. Momus holds his jester’s rattle aloft and strikes a pose as if to receive our applause. The scroll in his right hand announces the publication of a suite of costumes from the masked ball held at the palace of Saint-Cloud in the summer of 1752 to celebrate the Dauphin Louis’s recovery from smallpox.

|

|

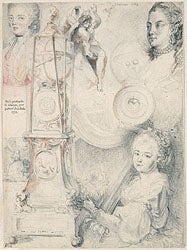

Sheet of Studies: Castel’s Clock, Various Portraits, and Carved Group, 1773

Black chalk, brush and gray wash, bister,

yellow and pink washes

Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts Graphiques,

Paris

|

This drawing is dominated by the standing astronomical clock at left — designed by Jacques-Thomas Castel (1710–1772), counselor-secretary to the king — that the artist would have seen at public auction in July 1773. The striking profile at upper right is of the actress Mademoiselle Clairon (1723–1803), copied from an engraving after Carle Van Loo’s portrait of her in the role of Medea. Flanking the clock is a detail of Marsy and Flamen’s sculpture of Boreas Abducting Oreithyia, one of the figural groups that adorned the Tuileries Gardens during Saint-Aubin’s lifetime. The identity of the woman at upper left is not known, but the charming young harpist at lower right is quite possibly a portrait of the artist’s eighteen-year-old niece, Rose de Saint-Aubin.

|

|

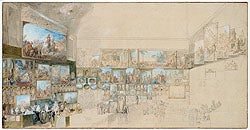

The “Salon du Louvre” in 1765, 1765

Pencil, watercolor, pen, and ink

Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts Graphiques, Paris

|

This unfinished watercolor records most of Jean- Baptiste-Siméon Chardin’s installation of the Salon of 1765, which consisted of some 420 works by 53 members of the Académie royale. Working from left to right, Saint-Aubin depicted the cluster of visitors who have come to the Louvre at midday: the time is indicated on the dial of Pajou’s model of a monumental clock case, seen halfway along the lateral wall at left. Such is the artist’s scrupulousness that every work illustrated can be identified.

|

|

Voltaire’s “Coronation” at the Théâtre Français on March 30, 1778,

1778

Watercolor over pen and ink, brush and gray wash

Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts Graphiques,

Paris

|

Saint-Aubin’s artistic tributes to his literary hero Voltaire culminated in the three late works exhibited together here. On the evening of March 30, 1778 (exactly two months before he died), Voltaire received two “spontaneous” ovations at the Théâtre Français during the sixth performance of his tragedy Irène: first when he entered his box and was crowned with a laurel wreath by the actor Brizard and the marquise de Villette and again immediately after the play when the entire company took turns crowning his portrait bust on stage. Saint-Aubin envisions both coronations as part of a single moment.

|

|

Society Promenade, 1760

Pen and brown and black ink, brush and gray wash,

watercolor, and gouache

The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

|

Saint-Aubin’s recurring theme is the juxtaposition of prosperous Parisians with those in humbler stations (the beggar at foreground left; an itinerant Savoyard family in the background, denoted by the hurdygurdy the woman is carrying). The artist’s exquisite pen work reinforces his preoccupation with details of clothing and coiffure, reflecting his commercial motivations for this work. He never designed anything so nearly resembling a fashion plate.

Major funding for Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (1724–1780) has been provided by The Florence Gould Foundation. Additional generous support has been provided by The Christian Humann Foundation, the Michel David-Weill Foundation, and The Grand Marnier Foundation.

|

|

The project is also supported, in part, by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. |

|