The Spanish Manner: Drawings from Ribera to Goya

October 5, 2010, through January 9, 2011

Exhibition Checklist: Goya's Drawings

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

Self-Portrait

c. 1798

Chalk over traces of pencil

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Walter C. Baker, 1971

CAT. NO. 33 |

Only a few years after the illness that left him

deaf, Francisco de Goya portrayed himself in the

fashionable garb and sideburns of a late eighteenth-century

gentleman. This drawing is the preliminary

design for the etching that served as the frontispiece

of Goya’s Caprichos, his series of eighty aquatint

etchings published in 1799. As a preparatory work,

the sheet provides an intimate glimpse of the artist’s

working process in red chalk.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

A Fight (Album B. 15)

1796–97

Brush and ink with wash

The Hispanic Society of America, New York

CAT. NO. 34 |

This extraordinary scene depicts a majo, the

fashionably dressed man reclining in front, watching

two women (or perhaps a man and a woman) brawl

on the floor. The delicacy and control of Goya’s

brushwork almost offset the violence of the scene,

in which one person raises a shoe to hit the other,

who grabs the first person’s hair. They are sprawled

on the ground, their garments raised and legs

intertwined, to the apparent amusement of the majo.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

Fatal desgracia. Toda la casa es un clamor, p.r q.e no à óbrado la Perrica en todo el dia (What a Disaster! The Whole House Is in an

Uproar Because the Poor Little Dog [Bitch]

Hasn’t Done Her Duty All Day) (Album B. 91)

1796–97

Brush and ink

Collection Michael and Judy Steinhardt, New York

CAT. NO. 35 (recto) |

Figures cry, pray, and count rosary beads, distraught

by the situation described in Goya’s caption. The

double-entendre of the word “Perrica” (little dog, or

bitch) suggests that their concern is not the animal

but the seated woman in tears — a prostitute with no

customers. The dog instead seems to play the role

of narrator as she is the only character who engages

the viewer.

|

|

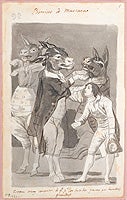

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

Borricos de Mascara. Estan muy contentos,

de q.e p.r los bestidos, pasan por hombres

grandes (Masquerading Asses. They Are

Pleased That Because of Their Clothing They

Are Taken for Grandees) (Album B. 92)

1796–97

Brush and ink, retouched with pen and ink

Collection Michael and Judy Steinhardt, New York

CAT. NO. 35 (verso) |

Goya identifies as “masquerading asses” both

the frocked donkeys and the obsequious young

man who is fooled by their attire, but whose own

finery may be considered equally superficial and

meaningless. When Goya returned to the drawing

to inscribe his caption, he took his pen to the image

and strengthened, with warm brown in, the lines

of the man’s hair and costume and the donkeys’ ears

and faces.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

Tuti li mundi (Peepshow) (Album C. 71)

1808–14

Pen, brush and ink with wash and crayon or chalk

The Hispanic Society of America, New York

CAT. NO. 36 |

While a man enjoys the view offered by a tuti li mundi — a term (literally meaning “all the world”)

for the kind of peepshow box pictured here — a

woman delights in a glimpse of his backside,

actively peering into the tear in his pants. The irony

implied is that the box offers something equally

lowbrow, absurd, or satiric, despite its claim to offer

the worldly and fantastic.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

Tiene prisa de e[s]capar

(She’s in a Hurry to Escape) (Album C. 128)

1808–14

Brush and ink with wash

The Hispanic Society of America, New York

CAT. NO. 37 |

Goya’s caption reinforces the worried look of this

young nun seen removing her habit. This scene of

“unfrocking,” symbolic of leaving a religious order,

may be a response to the secularization law that forced

monks and nuns out of monasteries and convents

during the Napoleonic era. Inventive touches — such as

the fallen cloak that doubles as the figure’s shadow —

temper Goya’s often strident anticlericalism.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

A Nude Woman Seated beside a Brook

(Album F. 32)

c. 1812–20

Brush and ink

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1935

CAT. NO. 38 |

Nudes are rare in Goya’s work, as are drawings in

which landscape figures prominently. The artist took

a painterly approach to the setting, covering most of

the paper with ink and allowing the exposed areas —

the woman’s bare flesh and the light shining through

the trees — to gleam in contrast. The onlooker in

the background suggests that the drawing could

represent the biblical story of Susanna and the Elders.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

Crowd in a Circle (Album F. 42)

c. 1812–20

Brush and ink

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1935

CAT. NO. 39 |

This drawing almost defies description. While the

circular composition perhaps relates to a dance,

the large number of figures and the open circle of

white space in the background suggest another

activity, perhaps one far less pleasant than dancing.

Figures in the right foreground appear to be

engaged in an argument.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

Repentance (Album F. 47)

c. 1812–20

Brush and ink with wash

Gregory Callimanopulos

CAT. NO. 40 |

An emaciated male penitent prays with clasped hands

in front of a makeshift cross. His gaping mouth and

lost gaze suggest a state of either ecstatic rapture

or vacant drowsiness. A rationalist with liberal sympathies, Goya satirized his contemporaries’

religious fanaticism in mordant drawings and

etchings that depict the exaggerated behaviors of

the overly devout. A few brushstrokes and effective

washes suggest the play of light on the rocky

surroundings, probably the entry to a hermit’s cave.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

Three Men Digging (Album F. 51)

1812–20

Brush and wash

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1935

CAT. NO. 41 |

This vigorous drawing has long been considered

a preliminary sketch for The Frick Collection’s

painting The Forge (on view in the East Gallery on

the main floor). The subtle changes that took place

between this triad of figures and their counterparts

in The Forge show the malleability and economy

of Goya’s pictorial thinking. Scenes from life and

imagination filled his albums and supplied him

with an endless source of material that could be

reworked to new ends.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

Torture of a Man (Album F. 56)

c. 1812–20

Brush and ink

The Hispanic Society of America, New York

CAT. NO. 42 |

Goya sketched scenes of violence and torture

throughout his career. Here, a man with his wrists

tied behind his back is being interrogated with

the help of the strappado, a device that causes a

painful dislocation of the shoulders and elbows.

By concealing the faces of the two men operating

the crank, Goya invites the viewer to concentrate

on the drama of the man kicking in midair, whose

gracefulness belies the horror of the scene.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

A Man Drinking from a Wineskin (Album F. 63)

c. 1812–20

Brush and ink, with scraping

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1935

CAT. NO. 43 |

The focus on the kneeling figure in the center of the

sheet, and his isolation in space without context

emphasize the loneliness of the endeavor. The large

wineskin, the man’s top hat, and his shadow are all

reinforced with saturated brushstrokes of darker

ink. Delicate strokes made with the point of a brush

define the crumpled cloth where he kneels.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

A Nun Frightened by a Ghost (Album F. 65)

c. 1812–20

Brush and ink with wash

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1935

CAT. NO. 44 |

In this ingenious portrayal of a nightmare apparition,

Goya used the wet point of his brush to depict the

phantom in transparent wash. The nun in the

foreground, confronting the apparition with her

hand raised, has been reinforced in darker wash.

A saturated brush full of ink created the rich, dark

contrast of her veil and the shadow under her hand.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

Beggar Holding a Stick in His Left Hand

(Album F. 70)

c. 1812–20

Brush and ink

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1935

CAT. NO. 45 |

Goya’s depictions of poverty are unflinching. Here,

an aged beggar fixes the viewer in his gaze while

extending his hat to receive alms. The shadows cast

by the man and his cane define the scene’s space and

increase its sense of stark isolation. This particular

type of representation may have been inspired by

etchings of solitary paupers by Rembrandt, an artist

Goya greatly admired.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

Peasant Carrying a Woman (Album F. 72)

1814–20

Brush and ink with wash

The Hispanic Society of America, New York

CAT. NO. 46 |

Goya’s ability to capture with split-second timing

images of figures engaged in vigorous activity

is matched here by his succinct execution. The

dynamism of the scene comes across immediately,

but the meaning remains obscure: is he assisting

or abducting her? Goya repeatedly focused on the

effect of gravity on the body. In such scenes as this

one, figures support each other and the weight of

the body is apparent.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

Two Prisoners in Irons (Album F. 80)

c. 1812–20

Brush and ink

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1935

CAT. NO. 47 |

Two prisoners, chained to a wall and shackled,

occupy the foreground of this sheet conceived in

light shadow. Daylight enters from the upper right

corner, where bars form a grid over the window, and

highlights the back of the adult figure. The adult

prisoner bends toward the figure of the similarly

chained child, casting a pool of shadow on the floor.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

The Anglers (Album F. a)

1814–20

Brush and wash

The Frick Collection, New York

CAT. NO. 48 |

Goya covered the writing on the top of this used

piece of paper with layers of wash. The resulting

shape appears to have suggested a grotto with

figures fishing. In contrast to the large wash areas,

he defines with the greatest precision the features of

a face, the details of a costume, and even the fishing

line with the tip of his brush, while leaving the fish

itself a mere blot.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

No llenas tanto la cesta (Don’t Fill the Basket So Full) (Album E. 8)

c. 1814–20

Brush and ink with wash, with scraping

Private collection, New York

CAT. NO. 49 |

An old woman huddles over her basket of eggs in

the lower third of the sheet in this brush and ink

wash from the “Black Border” Album. Goya’s

caption cautions against filling the basket too

full, an admonition or advice to the woman, who

appears self-contained, clutching the handle of her

basket. The meaning of the eggs, usually a sign of

promise and fertility, is ambiguous here.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

Mal tiempo pasas (You Are Having a Bad Time) (Album E. 26)

c. 1816–20

Brush and wash

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York,

Thaw Collection, gift in honor of the 75th anniversary

of the Morgan Library and the 50th anniversary of the

Association of Fellows. (1999.23)

CAT. NO. 50 |

Goya’s shepherd appears ragged and bent, while

his sheep rests. Christ told the parable of the Good

Shepherd, saying: “I am the Good Shepherd. The

good shepherd lays down his life for his sheep”

(John 10:11).

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

Pobre e gnuda bai filosofia (Poor and Bare

Goes Philosophy) (Album E. 28)

c. 1816–17

Brush and ink with wash

Collection Michael and Judy Steinhardt, New York

CAT. NO. 51 |

Does this peasant woman gaze upward in

bewilderment or in comprehension of the words

she has just read? Although Goya’s caption (a quote

from Petrarch, in faulty Italian) could be ironic, the

gleaming light that illuminates the figure’s face —

conveyed through the contrast of the exposed white

paper and the dark ink — suggests that this is a

scene of true personal enlightenment, which can be

experienced by all.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

Regozijo (Mirth) (Album D. 4)

c. 1816–20

Brush and ink with wash and chalk

The Hispanic Society of America, New York

CAT. NO. 52 |

Liberated from gravity and the limitations of

their aging bodies, two floating figures exchange

a touching look of shared delight. The woman’s

billowing skirt, rendered with bold dabs of ink

wash, conveys the speed of their magical ascension.

Goya’s numerous depictions of airborne figures are

roughly contemporary with experiments with hotair

balloons and parachutes in Europe, though here

he includes no such device. This couple’s levity is

pure fantasy. Fittingly, the man plays castanets,

a symbol of happiness or mirth.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

De esto nada se sabe (Nothing Is Known of This) (Album D. 7)

c. 1816–20

Brush and ink, with scraping

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1935

CAT. NO. 53 |

The caption of this drawing suggests that there is a

mystery inherent in the scene. The two figures in the

front appear to bend over a bundle of sorts. Behind

them, a singing or speaking figure emerges from the

arched doorway of a church, holding a piece of paper

with writing. There is an ominous tone, conveyed by

the gaping mouths and dark ink shadows.

|

|

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

Amaneció asi, mutilado, en Zaragoza, a

principios de 1700 (He Appeared Like This,

Mutilated, in Zaragoza, Early in 1700),

(Album G. 16)

1824–28

Crayon

Dian Woodner Collection, New York

CAT. NO. 54 |

Goya’s narrative caption recalls a horrible mutilation

that took place in his home town years before his

birth. Heavy strokes of black crayon at the bottom

of the bundle suggest blood pooled inside the fabric,

around the man’s protruding legs. This is one of

several drawings Goya made to comment on grisly

historical events he had heard of but not witnessed.

The exhibition is organized by Jonathan Brown, Carroll and Milton Petrie Professor of Fine Arts, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University;

Lisa A. Banner, independent scholar; and Susan Grace Galassi, Senior Curator at The Frick Collection.

The exhibition is made possible, in part, by the David L. Klein Jr. Foundation, Elizabeth and Jean-Marie Eveillard, and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

The accompanying catalogue has been generously underwritten by the Center for Spain in America. |