Domenico Tiepolo (1727–1804): A New Testament

October 24, 2006, through January 7, 2007

The eighteenth-century Venetian painter and draftsman Domenico Tiepolo is best known for his drawn narrative cycles of the commedia dell’arte character Punchinello and engaging scenes of everyday life in the Veneto. He reserved his greatest passion, however, for sacred subjects. This exhibition, organized by guest curator Adelheid Gealt, director of the Indiana University Art Museum, presents sixty key examples from Domenico’s New Testament cycle, his most extensive and least-known series of more than three hundred finished drawings illustrating the events of early Christianity through the foundation of the Church. Shortly after the artist’s death in 1804, the drawings, which were executed roughly between 1786 and 1790, were divided into two groups. The first group stayed together in an album (now in the Musée du Louvre), while the sheets from the second group were widely dispersed. The works were not recorded in Domenico’s lifetime, nor did the artist leave any clues as to their order, or even provide titles for them. So far, no patron for this vast undertaking has been discovered, nor has any motive other than the artist’s personal interest and deep piety emerged. The Frick exhibition is the first to present these works to the public.

This exhibition coincides with the publication by Dr. Gealt and George Knox, Professor Emeritus, University of British Columbia, of the catalogue raisonné of Domenico’s New Testament cycle — a monumental feat of art historical and biblical scholarship that brings together, for the first time, all 313 known sheets. Over the course of a decade, Gealt and Knox tracked down far-flung drawings, traced the scenes to their textual and visual sources, and assigned each sheet to its place in the series, which is the largest-known sacred cycle created by a single artist. Together, the exhibition and publication restore Domenico’s lost masterpiece to its original context. This exhibition coincides with the publication by Dr. Gealt and George Knox, Professor Emeritus, University of British Columbia, of the catalogue raisonné of Domenico’s New Testament cycle — a monumental feat of art historical and biblical scholarship that brings together, for the first time, all 313 known sheets. Over the course of a decade, Gealt and Knox tracked down far-flung drawings, traced the scenes to their textual and visual sources, and assigned each sheet to its place in the series, which is the largest-known sacred cycle created by a single artist. Together, the exhibition and publication restore Domenico’s lost masterpiece to its original context.

Domenico Tiepolo, born in 1727, was the eldest son and primary assistant of the celebrated master Giambattista Tiepolo (1696–1770), whose virtuosic frescoes adorn the ceilings of many of the great villas and churches of Europe. After retiring from painting in 1786, Domenico lived in relative seclusion on the family property outside Venice and devoted himself to his primary interest, his serial narratives composed of large finished drawings.

| |

|

|

|

| |

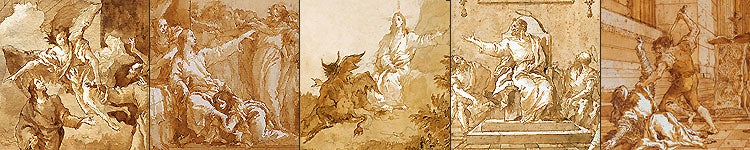

Domenico Tiepolo (1727–1804), The Presentation of Mary in the Temple, c. 1786–90, private collection, on loan to the Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington. All works illustrated are pen, ink, and wash over black chalk on paper. |

|

|

Domenico’s New Testament cycle is executed in black chalk, pen, brush, and ink on handmade paper. The individual drawings are approximately the same size (18 by 15 inches), and all are vertical in format. Domenico first lightly sketched out the composition (obviously conceived beforehand) in black chalk then went back over the lines in delicate, expressive strokes of the pen, adding layers of wash to give depth. Each sheet has a sense of completeness as well as connection with adjacent works. He made use of a wide array of compositional devices, gestures, and settings, and mined existing art — from early Christian to the works of his contemporaries — for inspiration. His most constant visual source was close at hand: the shimmering twelfth- to seventeenth-century mosaics of San Marco. Not only did they serve as starting points for many of his compositions, but the tesserae’s golden glow inspired him to tint many of his drawings a similar shade of sepia. The cycle as a whole bears the strong imprint of Domenico’s time and locale through references to familiar Venetian monuments and everyday life, as well as motifs from works by his father, Titian, Veronese, and other masters of the region.

|

|

|

|

| Tiepolo, The Flight into Egypt, after Castiglione, c. 1786–90, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; Photo credit: © 2006 by The Morgan Library & Museum |

|

|

|

Domenico’s epic begins with Christ’s ancestry. In The Presentation of Mary in the Temple (above), the quiet drama unfolds against a grand architectural setting. The child Mary, her back to the viewer, cuts a diagonal path up the fifteen steps to the portico of the temple, where the high priest, attended by patriarchs and a chorus of angels, awaits her with open arms. Mary’s parents, Anna and Joachim, and ordinary townspeople witness the event from the base of the stairs. Leaving the theatrical setting and large cast of characters behind, Domenico focuses on only a few figures in The Flight into Egypt, after Castiglione (right). Here, a weary Joseph and Mary, cradling her newborn baby in her arms, make their way across a rugged landscape, accompanied by the sheep they brought with them from Judea. In this sheet, Domenico borrows a composition directly from Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione (1609–1665), investing it with his own characteristic sense of humanity in a scene of great tenderness.

| |

|

|

|

| |

Tiepolo, The Calling of Matthew, c. 1786–90, The British Museum, London, National Art Collections Fund gift in honor of Sir Brinsley Ford; Photo credit: © The Trustees of The British Museum |

|

|

In numerous drawings, including The Calling of Matthew (right), Domenico sets his story in contemporary Venice. Domenico depicts Matthew ensconced at his desk in a banker’s office typical of the day, his ledgers open and a large safe to the side. Clients in fashionable Venetian dress stand before him as he counts out money. Only Matthew and the dog are aware of the entry of the disciples and Jesus, in incongruous biblical garb, who summons the future evangelist to follow him.

While The Calling of Matthew displays Domenico’s gifts as a storyteller and chronicler of his time, other sheets reveal his profound piety and depth of emotional connection with the suffering Christ. In one of the exhibition’s most moving drawings, Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane: The Second Prayer (brlow), taken from the story of Christ’s Passion, Domenico omits the usual accessory figures, choosing instead to concentrate on the anguish of a kneeling Jesus, arms upraised in fervent prayer as he confronts his imminent death.

| |

|

|

|

| |

Tiepolo, Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane: The Second Prayer, c. 1786–90, private collection on loan to the Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington |

|

|

Domenico approached his project as an interpreter and biblical scholar, drawing his own conclusions about the events he illustrated from the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, and the Acts of the Apostles — the standard sources for Christian imagery in Western art. Possibly beginning in Domenico’s time and culminating in the early nineteenth century, a shift in theological thinking took place, in which the Gospel of Mark began to be favored as the ur-text of Christianity over the Gospel of Matthew. Gealt and Knox’s analysis of the series brings to light Domenico’s particular reliance on the Gospel of Mark, Venice’s patron saint. Whether the artist was aware of these new currents of thought — possibly through his brother, a priest in the order of the Somaschi — or reached similar conclusions on his own is not known.

| |

|

|

|

|

Tiepolo, The Apostles Delivered from Prison, c. 1786–90, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts |

|

|

One of the ways in which Domenico demonstrates his adherence to Mark’s Gospel is through the frequent appearance of the Apostle Peter in the series. Peter, founder of the Christian Church, participated in and witnessed many of the events of Christ’s ministry and is traditionally believed to have dictated the Gospel to Mark. In one of many scenes illustrating the saint’s life, The Apostles Delivered from Prison (right), an older, frail Peter, preceded by John, is assisted by an angel over the threshold of a cavernous stone enclosure worthy of Piranesi. Two dogs, symbols of faithfulness and companionship, await them.

In addition to the Gospels, Domenico also turned to the more obscure apocryphal medieval devotional texts disavowed by the Catholic Church, such as the thirteenth-century Golden Legend, to infuse his cycle with a more complete and complex rendering of the Christian epic. These texts inspired some of Domenico’s most visionary works. In The Exaltation of the Sacrament (below), probably a description of the feast of the Eucharist from The Golden Legend, a crucifix rising from an altar is transformed into a vision of the Trinity. Here, a youthful Jesus, wearing a crown of thorns and holding aloft the chalice and wafer of the Sacrament, kneels on clouds before God, while the Holy Spirit and a chorus of angels hover above.

|

|

|

|

| Tiepolo, The Exaltation of the Sacrament, c. 1786–90, Bibliothèque municipale de Rouen |

|

|

|

Domenico’s New Testament cycle, carried out with obsessive focus over five or more years, is an intense affirmation of his faith and his culminating achievement as a draftsman. The series reveals his erudition and deep familiarity with a wide array of visual and literary sources, while his ability to sustain interest throughout a long sequence by using varied structures and emotional tone, much as a composer would in a suite of music, attests to his fertile imagination and powers of invention.

— Susan Grace Galassi, Curator

This exhibition has been organized by guest curator Adelheid Gealt and coordinated for The Frick Collection by Susan Grace Galassi. Principal funding for Domenico Tiepolo: A New Testament has been provided by The Peter Jay Sharp Foundation, with major support from the Homeland Foundation. Additional generous support has been provided by Lawrence and Julie Salander, the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, the Arthur Ross Foundation, The Helen Clay Frick Foundation, and the Fellows of The Frick Collection.

|

|

The project is also supported, in part, by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts, which believes that a great nation deserves great art. |

|