Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (1724–1780)

October 30, 2007, through January 27, 2008

|

|

|

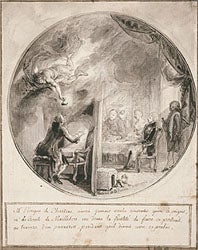

| Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (1724–1780), Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, Concealed behind a Screen, Making a Portrait of the Bishop of Chartres, 1768, pen and black ink and brush and gray wash over graphite, The Art Institute of Chicago |

|

|

|

For all its thematic sophistication and frequent visual complexity, Saint-Aubin’s art is, first and foremost, beautiful and engaging, brimming with humor and imagination. This is nowhere more apparent than in a drawing of 1768, Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, Concealed behind a Screen, Making a Portrait of the Bishop of Chartres (right). It records an unusual commission the artist received from the comte de Maillebois. According to the inscription beneath the drawing, Saint-Aubin was engaged to hide behind a screen at a dinner party to prepare secretly a portrait of the bishop of Chartres, who had previously refused to have his likeness taken. One wonders whether this elegant pen-and-wash drawing cleverly depicting the circumstance — with Saint-Aubin and his inspiring genius on one side of the screen, opposite the coconspirators seated at dinner with the unsuspecting bishop on the other — was as much a part of the assignment as the painted portrait, no trace of which has survived.

| |

|

|

|

| |

Saint-Aubin, Germain-Augustin and Rose de Saint-Aubin, Drawn by Their Uncle, 1766, brush and gray wash over black chalk and graphite, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

|

A more profound expression of the artist’s gifts as a portraitist is found in a dual likeness of his niece and nephew Rose and Germain-Augustin de Saint-Aubin (left). The young boy and girl are characterized with sincerity and respect, recalling Chardin’s attentiveness to the dignity of childhood. The sense of a moment suspended is enhanced by the way in which Rose holds the hurdy-gurdy resting in her lap, as if she were preparing to play. The artist’s special sensitivity to children points up the irony that he never married or had a family of his own.

There also may be a component of family portraiture in one of Saint-Aubin’s best known sheets, The Flirtatious Conversation (below right). It is a superb example of his inimitable painterly drawings, intricately layered with watercolor and gouache. He inscribed it with verses of his own composition, which translate: “Old, unreformed debauchee / You think you are seducing this beautiful creature / But long ago the damsel / Made up her mind to be honorable.” Saint-Aubin hereby creates an ostensibly conventional genre scene, entirely suitable for reproduction in an engraving. Yet the “old debauchee” bears a sneaking resemblance to known profile portraits of Saint-Aubin’s recently widowed elder brother Charles-Germain, then thirty-nine years old.

Next Page >>> 1 2 3 4

The accompanying catalogue is available, in both English and French, in the Museum Shop and on our Web site, at www.shopfrick.org.

Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (1724–1780) was organized for The Frick Collection by Colin B. Bailey, Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator, and Kim de Beaumont, Guest Curator; the curators at the Musée du Louvre are Pierre Rosenberg, President-Director Emeritus, and Christophe Leribault, Chief Curator in the Department of Drawings.

Major funding for Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (1724–1780) has been provided by The Florence Gould Foundation. Additional generous support has been provided by The Christian Humann Foundation, the Michel David-Weill Foundation, and The Grand Marnier Foundation.

|

|

The project is also supported, in part, by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. |

|