Watteau to Degas: French Drawings from the Frits Lugt Collection

October 6, 2009, through January 10, 2010

Part I (cat. nos. 1 to 31) | Part II (cat. nos. 32 to 63)

|

|

Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Three Standing Soldiers

c. 1715

Red chalk |

Watteau’s study of an infantry soldier in three different poses pays special attention to the model’s gestures as well as to his costume and armaments. The soldier is shown carrying his flintlock musket with its barrels facing the ground, a sword hanging from his waist belt — for use in close combat — and his ammunition bag, or cartouche, strapped on to his back. Despite the speed with which Watteau worked, we can make out a myriad of details, such as the pockets on the soldier’s jacket, the gaiters over his calves, and even the cockade on his three-cornered hat.

|

|

Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Standing Man (Persian)

1715

Red and black chalk |

This is one of nine figure studies by Watteau that can be associated with the state visit to Paris in 1715 of the Persian ambassador Mehemet Reza Beg, intendant of Erivan province — present-day Armenia — and his entourage of twenty men. Watteau’s handling of his two chalks is confident and extroverted, with black the dominant color. Was Watteau’s model a true citizen of the East — he has neither beard nor moustache — or did the artist dress one of his friends in a Persian costume from the store of theatrical accessories that he kept on hand in his studio?

|

|

Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Landscape with Bear Devouring a Goat

c. 1715–16

Red chalk |

This is Watteau’s copy after a lost pen-and-ink drawing by Titian that he studied in the collection of his patron, the wealthy banker Pierre Crozat — a collection especially rich in landscape drawings by the Venetian sixteenth-century masters Titian and Domenico Campagnola. Despite the fidelity of these copies, Watteau uses his red chalk to create an atmosphere and luminosity all his own. The naked onlooker of this gory scene — the figure at right whose face, buttocks, and knee are vividly accented — evokes the garden statuary that will later populate Watteau’s fêtes galantes.

|

|

Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Study for a Satyr about to Attack

c. 1717

Red, black, and white chalk |

An abrupt and energetic preparatory study for the figure of Jupiter in Watteau’s painting of Jupiter and Antiope in the Musée du Louvre, this drawing shows the undignified god “in a satyr’s image hidden” (Ovid), clambering to the top of a hillock and gazing down on the unseen sleeping Antiope below. Watteau here compresses the action and elongates the satyr’s outstretched right arm, with the white chalk between his second and third finger evoking the drapery that he will remove from his innocent victim.

|

|

Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Studies of Seven Heads

c. 1717–18

Red, black, and white chalk, graphite |

Studies of Seven Heads records the presence of three models: the beautiful, oval-faced girl in a narrow-strapped dress, seen in four different poses in the upper register; a square-faced girl with dark hair and the hint of a necklace, at lower left; and a young man with luxuriant eyelashes, whose head is studied twice. Despite the multiplicity of models, this drawing was probably made in a single session, rather than returned to over a period of time. Some of the heads can be associated with figures in the second version of Watteau’s Embarkation to Cythera in Schloss Charlottenburg, Berlin, painted for Jean de Julienne around 1717–18.

|

|

Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Woman Reclining on a Chaise Longue

c. 1718

Red and black chalk with stumping |

This drawing belongs to a series of female studies made in 1718 of a model hired by the comte de Caylus to pose in rented rooms for Watteau and a select number of his art-loving friends. Only after we realize that this day-dreaming young woman is shown with her nipples exposed do we become fully aware of the informality and eroticism of this sheet. Such is Watteau’s fluency in alternating between his red and black chalks that we do not immediately grasp that the red stripes at the top of the woman’s skirt are rendered in black, as are the creases of the garment below her waist.

|

|

Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Study of a Shell (Murex ramosus Linne)

c. 1720–30

Red and black chalk |

Study of a Shell is one of eight vigorous drawings of seashells, once thought to have been works of Watteau’s maturity, that are by an artist who still remains to be identified — possibly a designer of decorative objects or a sculptor. The shell itself has been reclassified as a marine gastropod of the subgenus Chicoreus, a species that provided the famous Tyrian purple dye of antiquity. The artist portrayed his specimens on a monumental scale: in reality, the shell represented here measured no more than three inches from top to bottom.

|

|

Pierre-Jean Mariette (1694–1775)

View of Crozat’s Gardens at Montmorency

dated 1724

Pen and brown ink, brown wash over black chalk, with highlights in white |

As noted in Mariette’s meticulous handwriting at upper left, this drawing of a group of trees towering over a low wall and a disappearing allée was done “in the gardens of M. Crozat at Montmorency” — the banker’s estate thirteen kilometers north of Paris. The eighteenth-century blue mount with its cartouche and framing lines is an example of Mariette’s distinctive manner of presenting his drawings. The epithet “ad vivum” (from life) on the mount’s cartouche confirms that Mariette made this drawing in situ, yet this garden scene adopts the style and handling of Annibale Carracci and Guercino, the seventeenth-century Bolognese masters whom Mariette most admired.

|

|

Étienne Jeaurat (1699–1789)

View of the Tiber, near the Ripa Grande, Rome

c. 1724–27

Gray ink and wash, white gouache on blue paper |

This quiet river view in mixed media on prepared blue paper was one of several landscapes that Jeaurat made during his student years in Rome as a pensionnaire of the French Academy. The eighteenth-century inscription at lower right on the edge of the mount identifies the site as the Ripa Grande, the larger of Rome’s two river ports at the foot of the Aventine Hill. This was a site under intense reconstruction during Jeaurat’s time in Rome, yet his view of the interlocking buildings in the late afternoon sun shows a lightly trafficked river and avoids engagement with the active, bustling port.

|

|

Jean-Baptiste Pater (1695–1736)

Standing Soldier with a Pipe

c. 1725–30

Red chalk |

Pater’s study of a soldier served to prepare the tricorne-wearing figure in at least two of his military pictures. As a former apprentice who reconciled with his master only in the last weeks of Watteau’s life, Pater acknowledged that he “owed everything he knew to this brief period of time” (Gersaint). Indeed, his bivouac scenes slavishly adhered to Watteau’s models. The soldier’s truncated hat at upper right confirms that this study has been cut down from a larger sheet. Nearly all of Pater’s military drawings once formed part of sheets of multiple studies in red chalk that were dismembered to produce single figures.

|

|

Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702–1789)

Frankish Woman from Galata and Her Servant

c. 1740–42

Black and red chalk on two sheets of paper, joined vertically |

Liotard’s exquisite drawing was extended by the artist by more than one-third on the left to include more of the mistress’s mantle and the sofa, thereby adding air and depth to the scene. It served as the design for an engraving produced for the Parisian print market in 1745. The legend accompanying the engraving offered a succinct description of the subject: “A Frankish Lady from Galata and her Slave who are about to go to Constantinople or another Turkish district. The Slave presents her Mistress with a veil similar to the one she wears on her face, without which Turkish women never go out.”

|

|

François Boucher (1703–1770)

Standing Woman Seen from Behind

c. 1742

Black, red, and white chalk, with stumping, on gray-brown paper |

Standing Woman Seen from Behind relates to the figure of a young woman who attends her seated mistress in A Lady Fastening Her Garter (“La Toilette”), 1742, in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. Strictly speaking, the Lugt drawing is not a preparatory study for the figure in the painting — there are too many variants between them — and may have served as an autonomous sheet, to be matted, framed, and displayed in the collector’s picture cabinet. The young woman is shown with her hips swaying to the left and wearing a sackback jacket, with double flounces from the elbow — the latest fashion in the early 1740s.

|

|

François Boucher (1703–1770)

View of a Rustic Habitation

c. 1760

Black and white chalk, gray wash and stumping, on blue paper, heightened with black pastel |

This atmospheric late drawing — in a superb state of conservation — shows rustic dwellings carved into the ruins of an ancient building, anchored by three prominent buttresses, heightened in white. At left, a faceless peasant woman ascends the steps, and various farmyard implements can be seen in the foreground. Unlike many of Boucher’s more finished landscape drawings, this sheet was not made to be engraved and was not preparatory for a painting. It is an example of an autonomous drawing, created for the market, and it was matted and mounted by the dealer Jean-Baptiste Glomy, whose blind stamp is preserved on the eighteenth-century mount.

|

|

Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686–1755)

Landscape with Bulls Fighting

dated 1751

Brush and black ink, gray wash, heightened with black and white gouache on brownish-gray paper |

In Oudry’s spectacular landscape, four beautiful— but hardly ferocious — bulls engage in an almost courtly encounter. The sheet, which is signed and dated at lower left, cannot be associated with a specific commission but may have been part of a volume that the artist assembled for his own use, consisting of “twenty-nine compositional drawings of animals.” When the contents of Oudry’s studio were sold after his death in July 1755, the drawing was one of eighteen works acquired for Christian Ludwig II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Oudry’s greatest patron after Louis XV. It remained in the ducal collections at Schwerin in northeast Germany until 1890.

|

|

Charles-Nicolas Cochin (1715–1790)

Portrait of Pierre-Jean Mariette

1756

Graphite with stumping |

Dealer, connoisseur, art historian, draftsman, and collector, Pierre-Jean Mariette (1694–1774) dominated the European art world in the middle decades of the eighteenth century. Cochin has portrayed him at sixty-two years of age, and this roundel drawing also served as the model for Augustin de Saint-Aubin’s engraving, made nine years later. Frits Lugt had an enormous admiration for Mariette, whom he considered a spiritual godfather of sorts. In the preface to the Louvre’s celebratory exhibition devoted to Mariette in 1967, Lugt signed himself “Votre très humble et très obéissant arrière-petit-fils” (Your most humble and most respectful great-grandson).

|

|

Charles-Nicolas Cochin (1715–1790)

Portrait of Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, Baron de l’Aulne

dated 1763

Graphite with stumping |

Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, baron de l’Aulne (1727–1781), was an economist, administrator, and reforming finance minister (contrôleur-général) in Louis XVI’s first cabinet. He was also the most distinguished occupant of the hôtel at 121, rue de Lille — where he resided between 1779 and 1781 — a complex of buildings that Lugt purchased in 1953 to house the Fondation Custodia. Cochin’s drawing shows Turgot with his side curls and long hair falling loosely onto his shoulders, his customary manner of presenting himself in public.

|

|

Charles-Joseph Natoire (1700–1777)

View of San Giovanni e Paolo in Rome

dated 1757

Brush and gray ink, brown and gray wash, pen and brown ink, and white gouache over black chalk |

Natoire’s fresh drawing on blue paper — which has been cut down on the left — was probably done in the autumn of 1757, after his recovery from a malignant fever. It shows the early Christian church of San Giovanni e Paolo, built around 410 on the site of the martyred saints’ residence and restored in the twelfth century. Natoire faithfully records the Clivus Scauri — a narrow, ancient street, crossed by arches — that ran along the church’s southern façade. One can see how Natoire first established his composition by a black-chalk underdrawing, and that he revised the figural groups, placing them closer to the drawing’s edge.

|

|

Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (1724–1780)

Le Boulevard

c. 1760

Pen and brown ink, gray and brown wash, over black chalk, with touches of watercolor |

“Parisians do not walk, they run, and are always in a hurry” (Sebastien Mercier, Tableau de Paris, 1783–89). Saint-Aubin’s joyful panorama shows citizens promenading on the fashionable tree-lined boulevard between the porte Saint-Antoine and the porte au Pont-aux-Choux in the east of Paris. The elegant couple in the center look warily in different directions as they cross the street; at left, youthful diners seated at table are approached by an aged beggar with a walking stick, who has just removed his hat.

|

|

Hubert Robert (1733–1808)

View of an Italian Garden

c. 1760

Red chalk |

Robert’s dazzling composition shows a moment of repose during an afternoon of tree husbandry. There are no gardeners in sight, but the propped ladder and scaffold on wheels on either side of the herm satyr have been used to shape the arbor that protects the dignified statue with upraised arm. This garden sculpture is based on a celebrated antiquity, the Minerva Giustiniani, which Robert would have seen indoors, in the gallery of the Palazzo Giustiniani in Rome. Robert’s insistent hatching lines on the edges of the sheet, independent of the motifs described, are characteristic of his most vigorous red-chalk Roman drawings.

|

|

Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806)

View of the Serapeum at Hadrian’s Villa

c. 1760

Red chalk, over black chalk underdrawing |

As a protégé of the abbé de Saint-Non, who had rented the Villa d’Este in Tivoli for the summer of 1760, Fragonard was invited to spend six weeks sketching in the Roman countryside. A small number of his drawings took as their subject views of the grounds of Hadrian’s Villa, four miles southwest of Tivoli. In this sheet Fragonard shows the ruins of a complex of buildings in the southern precinct known in the eighteenth century as the Canopus and thought to have been Hadrian’s re-creation of the Egyptian town and canal dedicated to the god Serapis.

|

|

Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806)

Le Calendrier des vieillards

c. 1780

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, over black chalk underdrawing |

This is Fragonard’s illustration of the eighth tale of Jean de La Fontaine’s Contes et nouvelles en vers, first published between 1664 and 1674. It is a cautionary tale about mismatched marriages. An elderly Pisan judge, Richard de Quinzica, has taken Bartholomée de Galandi, a beautiful, well¬born young woman, to be his much younger wife. Unwilling to perform his conjugal duties more than four times a year, he has created a calendar “Cluttered with dates demanding man’s abstention/ From husbandly pursuits.” The sheet was engraved for a two-volume illustrated edition of the Contes published in Paris in 1795.

|

|

Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806)

À Femme avare, galant escroc

c. 1780

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, over black chalk underdrawing |

The next tale in La Fontaine’s Contes concerns the well-matched couple Gulphar, “a knavish gent,” and the avaricious wife of a friend of his who is willing to become his lover only if he agrees to pay her two hundred crowns. Fragonard illustrates an episode not described in La Fontaine’s verses. In an opulent Parisian interior of the 1770s, Gulphar eagerly clasps his mistress around her waist, his eyes trained expectantly toward the sofa. She is in no hurry to respond to his advances and counts her money, crown by crown.

|

|

Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806)

Portrait of Fragonard Seated in an Armchair

dated 1789

Black chalk, over black chalk underdrawing |

The Latin inscription at the bottom of this sheet can be translated as “Fragonard drew himself in Bergeret’s home in the year 1789.” Fragonard’s host was his friend Pierre-Jacques Bergeret de Grancourt, a wealthy financier whose father had been one of the artist’s most fervent patrons. Fragonard was fifty-seven at the time, and we see him cross-legged and casually posed — perhaps recording his reflection as it appeared in one of his host’s mirrors. From contemporary documents we know that Fragonard was four feet eleven inches tall, had gray hair and eyebrows, a wide forehead, a medium-sized mouth, and a round chin — details captured in this most summary of self-portraits.

|

|

Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725–1805)

Female Nude Kneeling with Outstretched Arms

c. 1765–68

Red chalk |

Greuze’s vigorous, almost muscular nude study, done from life, was one of several such drawings in red chalk that he made in the late 1760s, while deciding on the subject of a history painting with which to be received as a full member of the Royal Academy. Although this female nude cannot be associated with a known composition, she seems to represent a supplicant young woman, in some anguish, who kneels at the foot of a bed, or against a slab of stone, and directs her outstretched arms and imploring expression toward an absent figure.

|

|

Jean-Pierre-Louis-Laurent Hoüel (1735–1813)

View of the Colosseum in Rome

c. 1769

Watercolor and gouache, pen and black ink, over a sketch in black chalk |

Hoüel portrays the towering Colosseum from the southeast, with a view of the masonry connecting the inner wall and the remains of the northern outer wall. The enormous arena, built between AD 70 and 80, had long fallen into decay; by the mid-eighteenth century it was forbidden to dismantle it further, and attempts were made to halt the detrimental overgrowth. This large, ambitious drawing began as a sketch in black chalk and was finished with the brush in a mixture of watercolors and gouache.

|

|

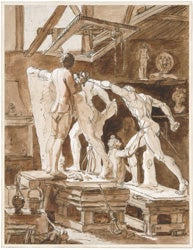

Esprit-Antoine Gibelin (1739–1813)

Interior of a Sculptor’s Atelier with the Borghese Gladiator

c. 1770

Pen and brown ink, brown wash over black chalk, on two pieces of paper, joined horizontally |

Gibelin’s drawing, done in Rome, shows the interior of a sculptor’s studio with the young master carving a life-size copy of the Borghese Gladiator from a block of marble. Both he and the marble block are placed somewhat precariously on top of a makeshift wooden pedestal. At right, an assistant measures the dimensions of the full-scale plaster model of the Borghese Gladiator that he will communicate to the sculptor. The wooden frame suspended above, with markings at regular intervals and plumb-lines hanging loose, would have been used at an earlier stage to delineate the various points on the marble block for roughing out the final composition.

|

|

Louis-Jacques Durameau (1733–1796)

Interior of a Paper Mill

c. 1770–80

Oil on paper |

In the background at right in Durameau’s oil sketch we see the rotating water beaters in front of which two shadowy figures are working in a vat. The first stirs the pulped fiber with his stick, the second dips his (unseen) mold into the mixture, from which the embryonic paper will be formed. The seated figure, with his back to us, is repairing a broken mold. On the back wall at left are sheets of paper hanging out to dry. The standing male figure in the center is possibly the mill master; the figure at lower right, crouching over a block of newly made paper, awaits his instructions.

|

|

Jean-Michel Moreau, known as Moreau le Jeune (1741–1814)

Portraits of the Artist’s Daughter Asleep

c. 1772

Pen and gray ink, gray wash, over black chalk |

The proud father has drawn his angelic two-year-old daughter, Catherine-Françoise Moreau (1770–1821), full-faced and fast asleep. Moreau le Jeune, the greatest book illustrator of his age, was an acolyte of the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who had campaigned against the evils of wet nursing. Certainly little Fanny (as she was known) seems well cared for and is neither constrained nor swaddled. But as the child of a fairly privileged Parisian family, she was dispatched to a wet nurse on the outskirts of the city, as her mother had been before her.

|

|

François-André Vincent (1746–1816)

Studies of Cats and a Donkey

dated 1772

Red and black chalk |

This is a composite drawing, mounted by the artist himself — who signed with a flourish at lower left — consisting of six sheets possibly cut from the pages of a sketchbook. Two different cats are studied: a rotund short-haired male, shown sleeping on the matted seat of a chair at upper left and again on the ground licking his paws; and a sleeker animal, preening himself in convoluted poses. In the vignette at upper right, Vincent revisits the cat’s ear and front paws, studying them as a history painter might study details of his model’s anatomy.

|

|

François-André Vincent (1746–1816)

Artists in a Landscape, near Tivoli

dated 1773

Black chalk and graphite |

In his view of two young artists sketching in the open air, Vincent avoided any hint of the picturesque villas and gardens that had attracted earlier generations of French artists to this hilltop town. His black-chalk drawing is quasi-documentary and his construction of space almost austere, with the empty white paper in the left foreground offering the most intensely lit section of the composition. Despite the rigor of this outdoor study, there is a touch of humor in the line of washing shown hanging out to dry by the entrance to the semicircular ruins.

|

|

Jacques-Louis David (1746–1825)

View across the Tiber with the Temple of Vesta

1775–80

Gray ink and gray wash over black chalk on two sheets of paper |

As a student at the French Academy in Rome, David frequently sketched urban scenes. To accommodate this panoramic vista of the west bank of the Tiber, he pasted two pieces of paper together. Among the recognizable Roman monuments are the round Temple of Vesta at right, and the semicircular opening of the sewer, the Cloaca Maxima, near the center. The relief-like composition and clear division of light and dark are elements of David’s emerging classicism.

Next >>> |