Watteau to Degas: French Drawings from the Frits Lugt Collection

October 6, 2009, through January 10, 2010

Part I (cat. nos. 1 to 31) | Part II (cat. nos. 32 to 63)

|

|

Pierre-Paul Prud’hon (1758–1823)

The Cellist, half-length, three-quarter back view, turned toward the left

1777–78

Pen and black ink, gray wash over graphite

|

The baron de Joursanvault of Beaune, an amateur musician and patron of the arts, commissioned twelve drawings from the young artist to illustrate his treatise on cello technique. Here, the baron also serves as the model. The strong contrast of light and dark and the sculptural quality of this drawing are characteristic of Prud’hon’s early work, which later gave way to a more fluid style.

|

|

Pierre-Paul Prud’hon (1758–1823)

Study for a Curtain

c. 1806

Black chalk, stumped, heightened with white chalk on blue paper (slightly discolored) |

This study was made for a detail in a painting executed by Prud’hon’s mistress and frequent collaborator, Constance Mayer. He deftly applied the chalk in a variety of ways — stumping (or blending) it in areas to create smooth transitions from light to dark and to render the texture and volume of the cloth, while depositing gossamer strokes of white elsewhere to suggest crackling light. The care he lavished on this one detail reveals his passion for drawing, his preferred medium.

|

|

Pierre-Paul Prud’hon (1758–1823)

Queen Hortense and Her Two Children in a Park

c. 1811

Black chalk, stumped, heightened with white chalk on blue paper, largely faded |

Prud’hon was a favorite painter of Napoleon and his wife Josephine. He made this preliminary drawing for a portrait of Queen Hortense of Holland, Josephine’s daughter by her first marriage, and two of her sons. The spontaneity of this sketch reveals the artist’s confidence as he works out a complex pyramidal composition. The writer Edmond de Goncourt described this drawing as being “executed with the audacity and brutality that only the great masters possess.”

|

|

Louis-Jean Desprez (1743–1804)

The Slaves of Vedius Pollio Thrown Alive to the Moray Eels

1777–79

Pen and gray ink, watercolor over traces of black chalk |

This delicate watercolor shows a gruesome scene: a slave is being flung into one of the fish tanks at the Villa Pausilypon, home of the notorious Publius Vedius Pollio — Roman equestrian, friend of the Emperor Augustus, and a man renowned for his wealth and cruelty. Vedius Pollio kept man-eating moray eels in his reservoirs “and was accustomed to throw to them such of his slaves as he desired to be put to death” (Cassius Dio, Roman History). Desprez’s drawing was among the many commissioned for a grandiose illustrated travel guide to Naples and Sicily, but the subject was finally considered too horrific for inclusion.

|

|

Nicolas Lavreince (1737–1807)

The Stolen Kiss

c. 1785–90

Pen and black and brown ink, brown and gray wash, heightened with white gouache |

In a fashionable interior, a smartly dressed man draws the standing woman close to him in order to steal a kiss. She is an amateur artist who paints for her own amusement; her female chaperone has fallen asleep at her sewing. The illicit interlude is witnessed by the disapproving figure in military costume who looks down on the couple from the overdoor at upper left — a portrait of the absent husband, perhaps. This ambitious gouache was probably intended as the model for an engraving; such gallant and licentious subjects proliferated in Paris during the 1780s.

|

|

Joseph Bidauld (1758–1846)

View in Rome

c. 1785–90

Watercolor, graphite underdrawing |

A leading landscape painter of his day, Bidauld looked back to the example of Poussin, as seen here in the careful balance of geometric shapes. This view was made during the requisite period of study at the French Academy in Rome — the center of the neoclassical landscape school. Following established practice, the artist sketched and painted directly from nature while traveling through Italy. This highly finished watercolor may have been completed in the studio.

|

|

Louis-Roland Trinquesse (c. 1746–c. 1800)

Portrait of a Man Looking Right

dated 12 October 1797

Red chalk |

Trinquesse’s male medallion portraits in red chalk were a specialty of his, and he nearly always signed and dated them within the framing lines, as is the case here. We do not know the identity of this handsome young man, who is shown informally with his hair unstyled and his collar without a cravate. Trinquesse uses intense parallel hatching lines to establish a luminous background in which the sitter’s face is almost chiseled in red chalk.

|

|

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867)

Medallion Portrait of Julie Forestier

1806

Graphite pencil, heightened with watercolor and white gouache on transfer paper, mounted on board |

Ingres traced the figure of his fiancée, the painter Julie Forestier, from a larger graphite drawing of her family. He applied watercolor to her hair and eyes and added white gouache highlights to her fashionable afternoon dress. Touches of gouache illuminate Julie’s eyes and earring and impart a slight shimmer to her lips. These changes transform the tracing into a unique work of art that rivals the fineness and intimacy of a painted miniature.

|

|

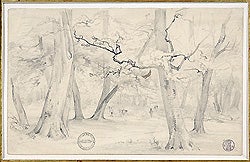

Théodore Géricault (1791–1824)

Forest with Two Figures and a Cow

c. 1813–14

Graphite |

This is one of a number of graphite studies the artist made in the parks around Paris. His direct observation of nature is evident in both the carefully shaded tree trunks and the free, zigzag strokes that suggest the textures of bark and lichen. In depicting only the trunks and low branches of the trees surrounding a small clearing, Géricault creates a sense of engulfment that is reinforced by the tiny scale of the background figures. This sous bois theme would become a favorite motif of the Barbizon painters.

|

|

Achille-Etna Michallon (1796–1822)

View from the Vatican

1818–21

Graphite |

This exacting view of Rome is rendered almost entirely in contour line, with limited shading. Although the emphasis is on the expansiveness of the view, rather than architectural description, several famous monuments can be discerned, among them, at left, the walls built by Urban VIII, with the Quirinale beyond, and at right the Capitoline Hill. Michallon’s many pencil landscapes recall the clarity of Ingres’s Roman sketches, which he may have seen as a pensionnaire at the French Academy.

|

|

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875)

Landscape with Rocks near Marino

dated 1827

Pencil on paper |

In this beautifully balanced composition, Corot gives equal value to the forest floor, the rocks, the trees actively straining toward the light, and the bare sky. His interest in different values of light and dark is evident at the center of the composition, where the boulders are built up with hard, fine lines and areas of soft, even shading. At this time, Corot was moving away from the precise neoclassical method of Ingres and Michallon toward a more tonal drawing style.

|

|

Louis-Gabriel-Eugène Isabey (1803–1886)

Boat in a Storm

c. 1828

Pen and brown ink, watercolor heightened with white gouache over black chalk underdrawing |

In this painterly sketch for an early oil painting, The Smugglers, Isabey laid in the dark setting with a few broad sweeps of the brush. Transparent, watery veils of gray wash suggest storm clouds and rolling waves, while denser layers of pigment are built up to indicate mountains. Using pen and ink, Isabey minutely outlines the smugglers with their booty and fragile oars in their desperate struggle against the elements — a quintessential Romantic subject.

|

|

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863)

Near Gibraltar

1832

Pastel and black chalk |

In this tranquil work, subtle gradations of blue unite land, water, and sky. The deftness of the artist’s hand is felt in the variety of strokes and tones of the pastel crayon. Delacroix made this drawing aboard ship while traveling to North Africa as part of a diplomatic mission. Pastel was the ideal medium for capturing en route transitory scenes of the rugged Spanish coastline, or to pass the time when becalmed, as he was here, near Gibraltar.

|

|

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863)

Study of a Wild Feline Facing Left Study of a Wild Feline Facing Right

c. 1847

Pen and brown ink |

In this pair of rapid sketches, the coiled energy of the panthers is perfectly expressed through the verve of Delacroix’s ductile line. Sweeping pen strokes establish the stalking animals’ silhouettes, while broad, energetic parallel hatching suggests their rippling muscles and shadows. The artist described his method of drawing in broken outlines as “coloristic” — an approach that runs counter to the neoclassicist’s pure, even line. Wild felines, a favorite Romantic motif, were of lifelong interest to Delacroix.

|

|

Hippolyte-Jean Flandrin (1809–1864) or Paul-Jean Flandrin (1811–1902)

View from the Summit of Vesuvius

1838

Watercolor over graphite or black chalk |

It is unclear whether this watercolor was made by Hippolyte-Jean Flandrin, best known for his religious murals, or his younger brother and frequent collaborator Paul-Jean, who painted academic landscapes. Produced when the brothers — both pupils of Ingres — traveled to southern Italy, this image of Mount Vesuvius exhibits cool neoclassical stasis rather than fiery chaos. The technique of building up dense pigment in short strokes emphasizes the mountains’ palpable solidity.

|

|

Théodore Rousseau (1812–1867)

Riverbank in Le Berri

1842

Watercolor, brown wash, heightened with oil in brown, blue, and white, over traces of black chalk |

Rousseau made this spare, lively sketch during a six-month sojourn in the unspoiled region of Le Berri in central France, where he continued working directly from nature. Leaving much of the sheet bare, he employed dashes, lines, and comma-like strokes to suggest the vitality and fullness of the trees. He reinforced certain areas with oil paint, which contributes to the scene’s luminosity. This sheet is an early example of his dessins-peints, a hybrid of oil sketching and drawing.

|

|

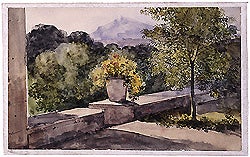

François-Marius Granet (1775–1849)

View of Mont Sainte-Victoire from the Terrace of Malvalat

1844?

Watercolor partially heightened with gum arabic, graphite underdrawing |

This radiant watercolor was painted from the terrace of Granet’s house, Le Petit Malvalat, near his native Aix-en-Provence, where he spent his later years. The view centers on the distant regional landmark, Mont Sainte-Victoire, represented in watery blue-violet strokes. The yellow flowers in the pot serve as a competing focal point in the foreground. Although Granet earned recognition during his lifetime for his quiet oil paintings of cloisters, his reputation today rests largely on the watercolors he made for pleasure.

|

|

Johan Barthold Jongkind (1819–1891)

View of Montmartre

c. 1849

Brush and brown ink, watercolor over black chalk |

Jongkind moved from his native Holland to the thriving artist’s community of Montmartre — then located outside the walls of Paris. The white substance in the foreground is probably gypsum, the primary ingredient for plaster of Paris, mined there in quantity. The drawing’s unprepossessing subject, low horizon, and glowing gold and green tones evoke Jongkind’s Dutch heritage. His loose, spontaneous handling of watercolor later earned him a reputation as a proto-Impressionist.

|

|

Jean-François Millet (1814–1875)

A Gleaner (study of Ruth for Harvesters Resting)

1851–53

Black conté crayon on beige paper |

This assured drawing is a study for the figure of Ruth in one of Millet’s most important paintings, Harvesters Resting, whose subject is taken from the Old Testament story of Ruth and Boaz. He blocks out the figure in straight, definite strokes, with particular attention to the pose and costume. For the glistening sheath of wheat, he uses an alternating pattern of bold lines juxtaposed with areas of untouched paper that serve as highlights. The figure’s face, in contrast, is delicately veiled in shadow.

|

|

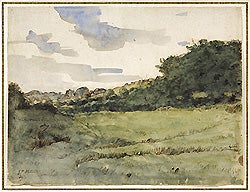

Jean-François Millet (1814–1875)

Landscape near Gruchy

c. 1854

Pen and brown ink, watercolor |

This previously unknown landscape was probably made in 1854 when Millet returned to Gruchy, the village of his birth. It is difficult to date with certainty, however, as the artist rarely combined the media he manipulates so masterfully here. The landscape is composed with color, its details only briefly indicated in pen and ink. The sheet is more of a painted composition than a drawing illuminated with watercolors.

|

|

Charles-François Daubigny (1817–1878)

View of Paris from the Tour Saint-Jacques

1852

Graphite with stumping on beige paper |

Known mainly as a landscape painter, Daubigny sustained himself as an illustrator. This detailed topographical drawing made from the top of the fifty-two-meter tower on the Right Bank preserves a view of the city just before Baron Haussmann’s radical restructuring took place. Soon the ramshackle area beneath the tower will be razed, and the congested neighborhoods surrounding the historic monuments visible here — the cathedral of Notre Dame and the Palais de Justice, and, further back, the Pantheon and the church of Saint Sulpice — will be opened up.

|

|

Auguste-Joseph Bracquemond, called Félix Bracquemond (1833–1914)

Portrait of Charles Daubigny (1817–1878)

1853

Lead pencil and graphite |

In this portrait of his friend, Bracquemond appropriately sets the artist before a loosely drawn forest, brushes and palette in hand. The leafy background, which reads both as the outdoors and as a landscape painting hung on a wall, alludes to Daubigny’s activity as a plein-air painter. Bracquemond achieves great tonal variation, from silvery gray to the deepest velvety black, and employs a wide range of drawing techniques, from the delicate hatching of the face to the bold, rapid strokes of costume and background.

|

|

Horace Vernet (1789–1863)

Study of Gabions in the Trenches of the Crimean War

1854–55

Pen and brown ink, brown and gray-brown wash, over traces of graphite on discolored paper |

This drawing relates to the siege of Sebastopol during which thousands of allied soldiers perished while waiting out the winter. The wicker baskets depicted here (gabions) were filled with dirt and rubble and used to line the trenches. Drawn by France’s premier war artist, this work may have been made on site during his visit to the Crimea, or from a photograph. This haunting image, with its debris, eerie stillness, and covering of snow, evokes the human suffering that took place in the desolate landscape.

|

|

Edgar Degas (1834–1917)

View of the Saône River with the Sérin Bridge near Lyon

1855

Black chalk on paper |

Although Degas is best known as a painter of figures, this sheet reveals his love of landscape. This rare, early drawing was produced on his trip to Lyon as an art student, and the balanced composition and purity of line reflect his classical training. Juxtaposing the empty foreground with densely packed buildings on the right, Degas leads the viewer through the landscape and emphasizes the vastness of space before him.

|

|

Edgar Degas (1834–1917)

Head of a Soldier

c. 1857–59

Watercolor, gouache, and red chalk wash over graphite |

It was during his trip to Italy in the 1850s that Degas produced this unique sheet with its unusual combination of media. Here he appears to draw from a mixture of Renaissance and Mannerist sources. The knight on horseback on the left is adapted from Paolo Uccello’s Battle at San Romano, while the central figure resembles Bronzino’s Portrait of Cosimo I in Armor. Degas combines his Old Master sources with a Romantic sense of drama and introspection, forming a creative synthesis in which imitation complements invention.

|

|

Léon Bonvin (1834–1866)

The Plain of Vaugirard

dated 1856

Black chalk with stumping |

This desolate scene represents the road alongside the Bonvin family’s inn on the outskirts of Paris. The drawing is striking for its radical simplicity of form, narrow tonal range, and variety of graphic effects. Bonvin lightly dragged the chalk broadside across the sheet to create a pearl-gray sky. With greater pressure, he achieves a deep velvety surface for the walls, and elsewhere suggests modulated light and dark by skimming the friable medium across the textured paper. The plunging perspective draws the viewer headlong to the distant horizon.

|

|

Paul Huet (1803–1869)

View near Apt

1862

Watercolor over black chalk |

This view of the south of France is typical of Huet’s proto-Impressionist approach. For the sky, he drags his wet brush in broad, unbroken strokes across the paper. Juxtaposed touches of green and black render the shapes of the trees and their shadows, both of which are reflected in the water at right. Exposed areas of the white paper appear as patches of sky, earth, water, and architecture brilliantly illuminated by the sun, imparting an intense luminosity to the scene.

|

|

Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (1814–1879)

View of the Alps

dated 1875

Watercolor heightened with yellow gouache over a pencil drawing on blue paper |

This sheet is one of some 600 drawings Viollet¬le-Duc made between 1868 and 1876 as part of his geological survey of the Massif du Mont Blanc in the Alps. Although the drawing’s function is scientific and documentary, as underscored by the annotations on the sheet—“gla” for glacier, “n” for neige (snow), and “porphire” for the reddish porphyry stone at top right—Viollet-le-Duc’s choice of vantage point and rendering of the scene reveal his aesthetic inclinations and superb draftsmanship.

|

|

Paul-Gustave Doré (1832–1883)

View of the Forest at Westbridge

dated 1879

Watercolor and gouache over graphite |

In this richly colored sheet, Doré focuses on the play of light filtered through the crowns of beech trees. Subtly varied tones of watercolor describe the glowing light on the upper portions of the trunks. Below, deep hues and touches of blue gouache suggest the murky shadows and cool, damp atmosphere in the heart of a dense forest interior, beyond the sun’s rays. The low vantage point and the vertical format of the sheet emphasize the height of the trees and suggest the forest’s endless depths.

|

|

Berthe Morisot (1841–1895)

Swans on the Lake of the Bois de Boulogne

1885

Pastel on blue paper (slightly discolored) |

The plein-air depiction of waterfowl was a favorite exercise of this member of the Impressionist circle. With an unrestrained hand, she runs the pastel across the paper in rapid scribbles, darts, and dashes, which suggest the vivid reflections of trees and sky in the water. A subtly blended passage describes the downy feathers of the swan at left, while a few quick strokes suffice for its companions.

|

|

Henri-Joseph Harpignies (1819–1916)

Studio of the Artist

dated 1909

Watercolor over black chalk |

In this charming view of the artist’s studio, various stages of the creative process are represented: the landscape sketch, the finished work, the matted drawing, and the prepared canvas, as yet untouched and leaning against the door. Harpignies plays with the concept of the painting as a window on the world and the boundary between interior and exterior space. A red and black cloak artfully draped on a chair represents the absent creator amid evidence of his work. |